It’s probably fair to say that no one loves their health insurance company. And over the past year negative sentiment seems to have risen to the boiling point. This was chillingly demonstrated by the social media reaction to the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December. It has been more conventionally apparent through a series of negative articles in the mainstream media including outlets like the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. President Trump (in reference specifically to the pharmacy benefit managers) talked of “the horrible middleman that makes more money, frankly, than the drug companies.” 1 And within Congress a number of regulations or funding changes have been floated that might impact the industry.

While we sympathize with consumers who have had difficult interactions with the healthcare system, we believe that much of the antipathy toward health insurers is misplaced. Their role as middlemen is a vital and increasingly important one in a U.S. healthcare system that struggles to balance between the incentives of providers (e.g., drug companies, hospitals, and doctors), payers (e.g., employers, the government, and individuals), and consumers. We believe managed care organizations, as they are more formally known, have the best aligned incentives. And we believe the allegations of bad behavior are largely misleading and exaggerated. Many of the legitimate complaints against the healthcare system get pinned on these companies only because they are the visible point of interaction, where in fact it is the provider or payer behind them that is driving the behavior. As investors, we observe that across industries middlemen are often high-quality businesses providing an important service while benefiting from network effects and scale economies to make the system more efficient (think for example, Costco or Visa). In managed care specifically, we see companies that play an essential role, have strong past and future growth rates, and trade at depressed multiples given the noise.

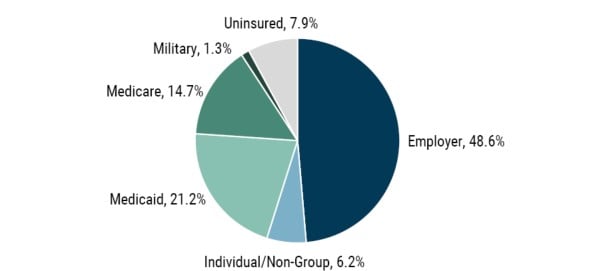

As background, most Americans receive their health insurance either from their employer or through a government-sponsored program (Exhibit 1). A smaller fraction pay for it directly, e.g., through health insurance exchanges. The largest government programs are Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare targets retirees, while Medicaid is directed at the lower income population. Virtually all the commercial insurance, and an increasing fraction of the government coverage, are administered by managed care organizations (MCOs). Most of the largest of these are for-profit listed companies, including UnitedHealth Group (the parent company of UnitedHealthcare), Elevance (who owns the Blue Cross Blue Shield brand in 14 states), Cigna, CVS (though their Aetna subsidiary), Humana, Centene, and Molina.

Exhibit 1: Health Insurance Coverage of U.S. Population

As of 12/31/2023 | Source: KFF, Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population

Sentiment Toward the Industry

We break the major critiques into three broad categories:

- Health insurance companies are overcharging the government, e.g., by “coding” Medicare beneficiaries for conditions that are not being treated.

- Health insurance companies are not fulfilling their obligations to consumers, e.g., by denying claims.

- The pharmacy benefit, in particular, is managed in a way to drive up drug costs for consumers and payers.

Coding Controversies

The Wall Street Journal published an article in February that delved into the somewhat arcane issue of Medicare coding. 2 When an eligible retiree opts into the Medicare Advantage 3 system with a particular insurer, the government pays that insurer a per-member per-month premium. That premium varies based on how the member has been coded through the assignment of diagnoses for health conditions that on average lead to higher medical costs. We believe the article was slanted and unduly negative in how it characterized coding.

Coding is a long established and well understood practice. It is logical for more risky individuals to have higher levels of government reimbursement. Were this not the case, those riskier individuals would have difficulty obtaining coverage. The coding is regulated and routinely audited by the government. In many cases, the coding is done by outside physicians. Articles in the popular press often point to the fact that the patients may not be treated for the specific condition being diagnosed with coding. But that’s not the point. Coding is based on a correlation to future healthcare costs rather than the cost of treating a specific condition.

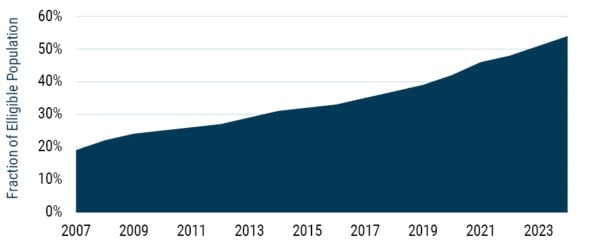

In this model of fixed payment per member, the insurers are incented to address conditions proactively rather than allow things to get worse later. That is the opposite of the somewhat perverse incentive of the traditional fee-for-service healthcare system where players maximize revenue by conducting more treatment, even beyond medical benefit and cost effectiveness. Consumers have been voting with their feet and increasingly opting into Medicare Advantage, which now has exceeded 50% penetration across the eligible population (Exhibit 2). Clearly people value the wider range of benefits and lower deductibles that offset the potential inconvenience around narrow networks and practices like prior-authorization requirements.

Ultimately, the insurers are regulated, and reimbursement is set to achieve a level of medical loss ratio – the fraction of premiums paid out as benefits. For example, last year the government enacted a set of reductions to Medicare reimbursements, referred to as “V28,” that fine-tuned coding and lowered government costs. So the motivation and benefit for abusing coding over time is limited. And commentary that Medicare Advantage costs the government more than traditional fee-for-service Medicare is not based on rigorous analysis and ignores the out-of-pocket savings to the members. We believe Medicare Advantage costs the system less and there is therefore good reason for its increasing prevalence. With tens of millions of members, there will always be individual cases that don’t smell right, but we know of no convincing evidence of systematic malfeasance or misdiagnosis in coding.

Exhibit 2: Medicare Advantage Penetration

As of 12/31/2024 | Source: KFF, Medicare Advantage in 2024

Denial of Claims

More broadly, there is the narrative that health insurers are putting up barriers to reduce the benefits they pay. This view is based on an intuitive but not entirely correct assumption that it is in the insurance companies’ self interest to deny claims and thus increase their profits. This is overly simplistic. The business model of an MCO is better thought of as administrative and consultative rather than as pure insurance. It is not these companies who ultimately pay for healthcare, it is their clients. This is most obvious with employer-sponsored health insurance, where the majority of benefits are self-insured by the employer, and the “insurers” provide administrative services. Even for other commercial or government programs where the MCOs take risk, it is very short tail risk as the contracts re-price annually. And the companies are explicitly or implicitly regulated to relatively low profit margins (which in fact were close to zero on government programs in 2024 given post-Covid dynamics). This means the long-term benefit of denying coverage is limited.

In reality, the management of care (e.g., through redirecting the site of care, prior authorization requirements, higher deductibles, or at-the-counter costs for prescription medicines) is done on behalf of the insurance companies’ clients, the commercial or government payers. These clients ask for and value this service to reduce their medical costs and put some skin in the game for consumers. And as is evident with the increasing Medicare Advantage enrollment, consumers seem to accept these practices as they are allowed to share in the savings through lower co-pays or extended coverage of preventative healthcare (e.g., annual physicals or supplemental benefits like health club memberships).

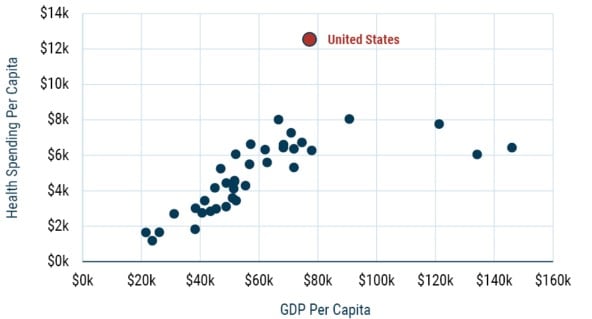

The big-picture observation is that the facts don’t support claims of denied healthcare. The level of healthcare spend in the U.S. is high and increasing. The U.S. spends more per capita than other nations (Exhibit 3), and profit margins for health insurers are modest. By all appearances the need is for more care management, not less. In fact, less than 1% of claims are denied for medical necessity. And even in those cases, it is a mistake to assume these denials are “wrong.” The providers have the perverse (from a societal perspective) incentive to over-diagnose and over-treat.

Exhibit 3: Healthcare Spending across OECD Nations*

As of 12/31/2022 | Source: Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker

*The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) comprises 38 wealthy democratic countries.

PBMs and Drug Pricing

Turning to the pharmacy benefit, there is no doubt that drug costs are rising over time. In many ways this is a good thing as innovation has led to great advances in treatment. The pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) run by the insurers get blamed (often by drug companies) for high drug prices. We sit on both sides of this finger pointing as we are investors in both pharma companies and in the MCOs that have PBM subsidiaries. From our perspective, drug prices are high because pharma companies charge a lot for drugs. To be clear, we don’t think that’s inherently unreasonable or unethical. After all, iPhone prices are high because Apple charges a lot for iPhones. And pharma companies have high research costs and must support many products that never make it to market. But it seems strange to think the blame for the costs should fall to a lower profit margin intermediary. The PBMs function to negotiate prices down, partly through their scale, but also by setting the “formulary” that manages which drugs are applied, and in what order, and at what costs. This is an important tool to driving volume to equally effective generics, and now biosimilars, 4 to reduce overall costs without impacting efficacy.

One reason the PBMs have been under suspicion is the complexity and lack of transparency in the economics of how exactly they get paid. And these mechanics can produce some perverse outcomes. As an example, historical practice for drug pricing is to use “spread pricing” and “rebates,” where the drug company sets a relatively high list price, and the PBM negotiates a discount on behalf of their clients. That discount is implemented as a rebate that flows primarily back to the payer (e.g., your employer) through the PBM. A hitch is that a consumer at the pharmacy counter might have a co-pay or deductible based on a high list price. There are examples of cases where this leads to a higher cost at the counter than if the consumer bought the drug without insurance. So where is this extra money going that is seemingly taken out of the consumer’s pocket? First order, it is going to the payer! Your company may be making an explicit decision to keep its cost of medical benefits manageable by having a higher burden on the consumers who use them. They could have those rebates passed on to the consumer at the pharmacy counter, but they would rather have them for themselves, so they instruct the PBM to do their bidding. It is the nature of insurance that the healthy people subsidize the sicker ones. In this example, the payers are choosing to partially unwind that. In any case, this issue is more about the payer than the PBM acting as an agent. In fact, all major PBMs offer and even promote programs that don’t use rebates and where they get paid more on a fee-for-service basis. To the extent that rebates live on (this is one area where legislative action seems possible), it is not the PBMs who are pushing for it.

Current Political Environment

It is hard to write about government policy without the risk of becoming obsolete the next day. But we think the current discussions in Washington will not meaningly change the economics of the industry. Medicare Advantage has long been a favored program of Republicans as a free market solution, and the benefits do not appear to be under threat. President Trump has also expressed opposition to Medicaid cuts. As the insurance coverage for over 20% of Americans (and more in red states), it is a dangerous program to touch. Republicans remember how the Democrats regained control of the House of Representatives in 2018 campaigning on healthcare.

Still, Congress has focused on Medicaid to look for budget savings (at least on paper) to pay for tax cuts. We believe the focus is not as much on cutting actual healthcare coverage, but instead the prime target is administrative costs within the government and “fraud and abuse.” Realistic reductions to Medicaid seem to focus on work requirements (which would not be a substantive hit to the MCOs) or to reducing so-called provider taxes. Provider taxes are the eyebrow-raising practice in which States gross up the payments they make to Medicaid providers (thus generating a higher dollar value from a fixed percentage match from the federal government) and then recoup that additional reimbursement through higher taxes on the provider.

PBM reform has been on the table for a long time. It is possible something happens legislatively, but the companies are well prepared to adjust to reasonable changes. While the government may not realize it, proposed changes like eliminating rebates are really more targeted at the payers than at the PBMs. Proposed legislation for the Warren-Hawley bill (to force separation of PBMs from pharmacies) seems more like political posturing rather than realistic policy.

Conclusions

Charlie Munger famously remarked, “Show me the incentives, and I’ll show you the behavior.” If you think about the incentives of health insurers, it is largely to maximize their membership and develop ancillary services given that their profit margins are allowed to vary within a fairly limited corridor. This type of growth is achieved through providing benefits that satisfy both customers and payers, which means providing better health outcomes, better customer service, and lower costs (sometimes referred to as the “triple aim” of healthcare). Contrast that to the traditional fee-for-service model still employed in government-sponsored Medicare, for example, where healthcare providers are motivated to maximize cost by providing as much healthcare as possible. While that might have some correlation to outcomes, the incentive is to overshoot, leading to no better (or worse?) results for consumers and increased cost to the system. If journalists spent as much time scrutinizing hospitals and doctors, they would no doubt find some bad anecdotes there.

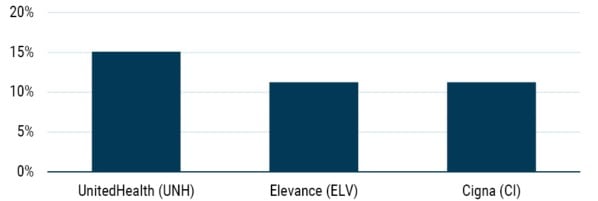

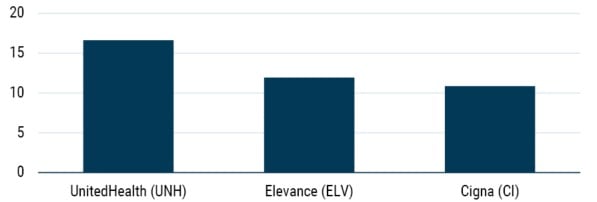

Behind all the noise, there are many fundamental tailwinds to the industry. Innovation in healthcare is a great thing, and the rising expense on healthcare is not bad when it comes with better outcomes. And innovation increases the need for the spend to be managed as well as the role of the MCOs that sit at the center of the system. This increase in importance, as well as demographic drivers, has played out through the companies’ strong fundamental performance. They have had double-digit EPS growth over the long term. And while Covid was a significant disruption in both positive and negative ways, this growth is largely not geared to the economic cycle. It comes at multiples that are not demanding and at a high return on incremental capital. The three stocks we hold in the GMO Quality Strategy have compounded EPS growth at double-digit rates over the long term (Exhibit 4), and as of this writing, trade at a P/E that is almost the same (i.e., a PEG ratio of 1) (Exhibit 5). For investors willing to wait until the storm passes and the headlines fade, we believe the fundamentals will drive an attractive return from this sector.

Exhibit 4: 15-Year EPS Compound Annual Growth Rate

As of 3/11/2025 | Source: Bloomberg

Exhibit 5: Consensus 2025 P/E

As of 3/22/2025 | Source: Bloomberg

Download article here.

It is unclear what President Trump’s comment is getting at, since it is not accurate looking at either total earnings or profit margins.

Weaver and Mathews, "DOJ Investigates Medicare Billing Practices at UnitedHealth," Wall Street Journal, February 21, 2025.

Americans eligible for the government-run Medicare program have the option to enroll in privately managed “Medicare Advantage” plans, also known as “Medicare Part C.” These typically come with a wider range of benefits and lower co-pays, with the tradeoff that consumers may be directed to in-network providers and in some instances be required to go through more steps to authorize care.

Biosimilars are copycat drugs that can be brought to market when the patent expires on a complex “biologic” drug, such as Abbvie’s Humira. Biologics are made from living organisms. Unlike generics, biosimilars are not exact copies, but have been approved as close enough to be a legitimate lower-cost substitute.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are the views of Tom Hancock, Ty Cobb, and Anthony Hene through the period ending March 2025 and are subject to change at any time based on market and other conditions. This is not an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security and should not be construed as such. References to specific securities and issuers are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations to purchase or sell such securities.

Copyright © 2025 by GMO LLC. All rights reserved.

It is unclear what President Trump’s comment is getting at, since it is not accurate looking at either total earnings or profit margins.

Weaver and Mathews, "DOJ Investigates Medicare Billing Practices at UnitedHealth," Wall Street Journal, February 21, 2025.

Americans eligible for the government-run Medicare program have the option to enroll in privately managed “Medicare Advantage” plans, also known as “Medicare Part C.” These typically come with a wider range of benefits and lower co-pays, with the tradeoff that consumers may be directed to in-network providers and in some instances be required to go through more steps to authorize care.

Biosimilars are copycat drugs that can be brought to market when the patent expires on a complex “biologic” drug, such as Abbvie’s Humira. Biologics are made from living organisms. Unlike generics, biosimilars are not exact copies, but have been approved as close enough to be a legitimate lower-cost substitute.